![]() |

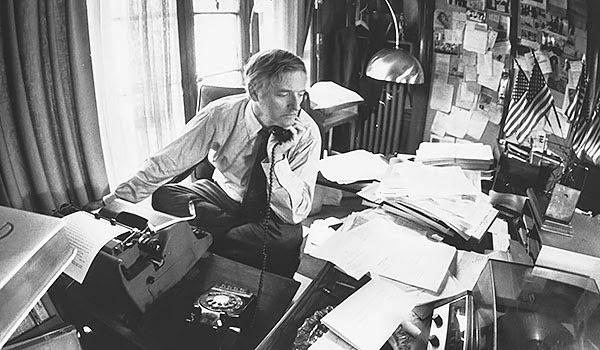

| Jim Kaat pitched for an amazing 25 seasons. |

![]() |

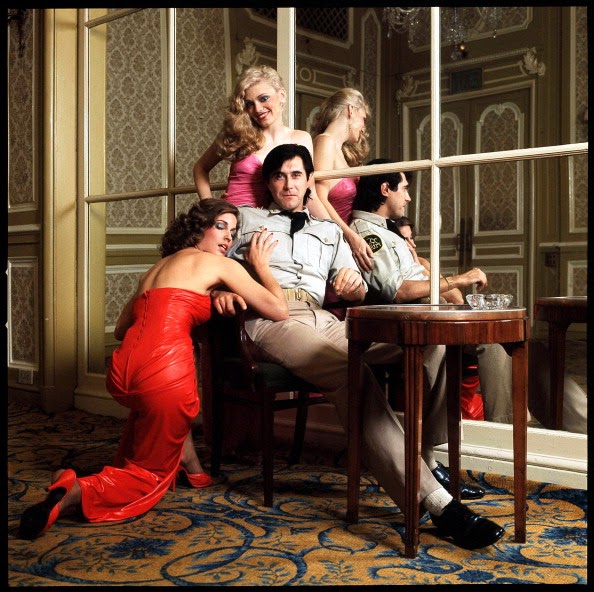

| Tony Oliva, with the Twins in the 1960's. Oliva won 3 AL batting titles. |

![]() |

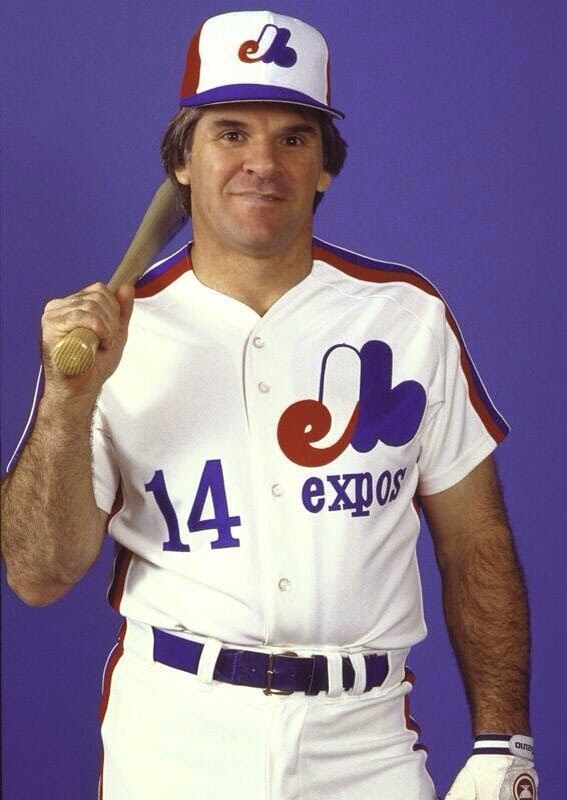

| Me and Tony O, 2012. He is one of the nicest athletes I've ever met. |

![]() |

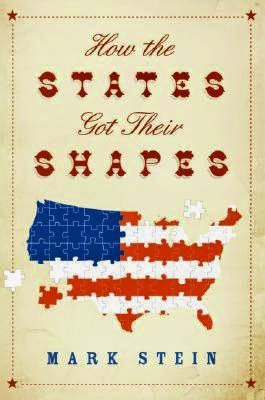

| Gil Hodges, first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers. |

![]() |

| Ken Boyer, third baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals. |

Like many baseball fans, I was disappointed when the Golden Era Committee for the Hall of Fame announced on December 8ththat no one had been elected to the Hall of Fame. The Golden Era Committee examined players who made their primary contribution to baseball between 1947 and 1972. The Committee had nine players on their ballot, along with former Cincinnati Reds general manager Bob Howsam.

Baseball writer Joe Posnanski had a great post about

the math behind the Golden Era Committee, and why it was almost impossible for them to elect anyone. The members of the committee were limited to voting for just four players, which lessened the chance of anyone being elected.

As a Minnesota Twins fan, I really wanted to see Tony Oliva and Jim Kaat get elected. In my Hall of Fame philosophy, I’m more of a “big Hall” kind of guy. I feel that there are a number of really excellent players who deserve to be in the Hall of Fame, like Jim Kaat, Tommy John, Vada Pinson, Al Oliver, Ted Simmons, Tim Raines, Dave Parker, and Fred McGriff. That being said, there are a number of players in the Hall of Fame who I think don’t belong. I don’t think they should be removed from the Hall of Fame, but I think they were bad choices. Most of these players were selected by some form of the Veterans Committee. My list of Hall of Famers who don’t belong would include: Chick Hafey, Jesse Haines, Fred Lindstrom, Travis Jackson, George Kelly, George Kell, Addie Joss, Rick Ferrell, Ray Schalk, and Dave Bancroft.

It annoys me when people say or write things like “The Hall of Fame is for players like Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle.” Well, yes, but it’s also for players like Billy Williams, Goose Goslin, and Bert Blyleven. There are 211 players in the Hall of Fame. Obviously, not all of them can be as great as Mays and Mantle. You can have a Hall of Fame in your mind that is only made up of Mays, Mantle, Hank Aaron, and other players who were first-ballot, no doubt about it Hall of Famers, as long as you know that your Hall of Fame does not bear any resemblance to the actual Hall of Fame. You can’t stick your head in the sand and pretend that the bottom barrel HOFers don’t exist. But, at the same time, we shouldn’t use those bottom barrel players as benchmarks for who to elect in the future. If we start putting in everyone who is better than the worst Hall of Famer, we’ll have a Hall of Fame that will be overstuffed.

The “Golden Era” ballot of 2014 was full of very good candidates who all have their pluses and minuses. You can make really good arguments for or against all of these players. Here are my thoughts on the candidates on the ballot, except for Bob Howsam, who I don’t have an opinion on. I don’t think executives should be on the same ballot as players.

Dick Allen: No matter where Dick Allen played, controversy followed him. Allen was one of the best sluggers of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. But injuries and Allen’s knack for pissing off every team he ever played for led to him playing his last game at the age of 35. I understand that Allen was a really great player, and he was definitely one of the best players in baseball from 1964-1974, but his counting numbers are really low for the Hall of Fame. Allen finished his career with just 1,848 hits and 1,119 RBIs. There are 178 players who have played from 1901 to the present who have more than 1,800 hits and 1,100 RBIs, which doesn’t exactly scream “elite player.” Allen’s Hall of Fame case is all about his hitting, as he was at best an indifferent fielder. He has negative fielding WAR for every season except 1964, when he has a paltry 0.3. I get that Allen’s peak as a player was really high, but I just have a problem with putting someone in the Hall whose counting stats look like Lee May’s.

There’s a great bio of Dick Allen on the SABR website, which helped me understand more about some of the controversies surrounding Allen’s career:

Ken Boyer: From 1956-64, Boyer was one of the game’s best third basemen, putting up 8 seasons of 90+ RBIs, and leading the NL in RBIs in 1964 with 119, the same year he won the MVP award and led the St. Louis Cardinals to the World Series. Boyer’s peak is very impressive, but unfortunately the magic quickly faded, and Boyer’s career from 1965-69 was undistinguished. I think Boyer was a great player, but for me he falls short of being a Hall of Famer.

Gil Hodges: Another great player with a terrific peak but a shorter career, Hodges was the slugging first baseman for the “Boys of Summer” Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1950’s. Hodges put up 7 consecutive seasons of 100+ RBIs, and when he ended his playing career in 1963 his 370 home runs were good for 10

th on the all-time list. Hodges faded quickly after his age 35 season in 1959. Hodges has been one of the most discussed Hall of Fame candidates, as he has consistently fallen just short of election time and again. In his 15 years on the BBWAA ballot, Hodges was named on more than 50% of the ballots 11 times, so it’s pretty crazy that he didn’t get in. As Joe Posnanski

points out in this excellent blog post, every player who has received 50% of the BBWAA vote, except for Hodges and Jack Morris, has been eventually elected to the Hall of Fame, either by the BBWAA or by some incarnation of the Veterans Committee. Everybody liked Gil Hodges, and by all accounts he was a really great guy, which you think would have helped him get elected to the Hall. Hodges also managed the “Miracle Mets” in 1969, and he died young, of a sudden heart attack at age 47 in 1972. He was considered one of the best fielding first baseman of his era, winning 3 Gold Gloves, even though the award wasn’t established until 1957. For me, Hodges falls just short of a Hall of Fame career.

Jim Kaat: One of the most durable pitchers ever, Kaat pitched for 25 seasons, from 1959 to 1983. At 283 wins, he fell short of the magic number of 300, and I think that has kept him out of the Hall. Let’s say, hypothetically, that Kaat lost one close game every year of his career. If we could give Kaat that one more win for each year of his career, he’d be at 308 wins and would be in the Hall of Fame for sure. So if Kaat would have been a Hall of Famer with just 17 more wins, why is he not a Hall of Famer at 283 wins? I don’t know exactly how sportswriters would answer that question, but I have some ideas. Kaat was not an overpowering pitcher, and he didn’t have much of a peak to his career. He was a compiler, putting up big numbers through longevity, not sheer dominance. He wasn’t Tom Seaver. Kaat won 16 Gold Gloves in a row, and he was such a good athlete that he was used as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner in 106 games during his career. Unfortunately, Kaat got injured during the 1972 season while pinch-running, and that no doubt cost him several wins, as he was 10-2 with a 2.06 ERA when he got injured. Kaat might have lost some support for the Hall of Fame because he spent the last five years of his career as a swingman alternating between the bullpen and spot starting. Voters might have seen Kaat as just hanging on too long trying to get to 300 wins. Personally, I would love to see Jim Kaat in the Hall of Fame. He was a great pitcher and he’s been a great broadcaster for many years.

Minnie Minoso: While some fans might remember Minoso for his publicity stunt pinch-hitting appearances with the White Sox in 1976 and 1980, he was actually one of the best players in the American League during the 1950’s. Like practically every other player on this ballot, Minoso faded quickly after age 35, which is ironic, given his late-career pinch-hitting appearances. But during his prime, Minoso was a 9-time All-Star, and a three time Gold Glove winner. Minoso also finished 4th in the MVP voting 4 times. Oh, and he has the same number of 100+ RBI seasons as Mickey Mantle: 4. Should Minoso be in the Hall? Again, I think he falls just short.

Tony Oliva: Tony O is one of the nicest guys I have ever met. I’ve had the pleasure of meeting Tony several times over the past few years, and he always has a huge smile on his face, ready to talk about baseball or the cold Minnesota weather. My favorite story about meeting Tony was one cold April day when my wife and I were walking to our seats at Target Field. We had just passed Tony O’s Cuban sandwich stand, and I was telling my wife what a great player Tony Oliva was in his prime. And then of a sudden, as if on cue, Tony O was right there at the next section of seats! It was pretty cool. So I admit, I’m a Twins fan, and I’m biased, I’d love to see Tony Oliva elected to the Hall of Fame. He was a great player and he’s a really wonderful person. I know that Oliva’s peak as a player was short, but he was one of the best hitters in baseball during the offensively challenged 1960’s. If Oliva hadn’t gotten injured and messed up his knee in 1971, I think he would have been in the Hall of Fame a long time ago. Despite the brevity of Oliva’s career, he had many highlights, as he was an 8-time All-Star, won three batting titles, led the league in hits five times, and in doubles three times.

Billy Pierce: Pierce was one of the best left-handed starting pitchers in the American League during the 1950’s. Pitching for the White Sox, Pierce led the league in wins in 1957, and won the ERA crown in 1955. Pierce was an excellent pitcher, and his career record of 211-169 is quite similar to Hall of Famer Don Drysdale, who had a record of 209-166. I think Pierce was very good, but not a Hall of Famer.

Luis Tiant: Tiant was a superb pitcher in the 1960’s, winning 21 games and leading the American League in ERA in 1968. After injuries sidelined him for much of 1970 and 1971, Tiant returned with an array of different windups and deliveries, and he was able to rejuvenate his career. Tiant went on to win 20 games for the Red Sox in 1973, 1974, and 1976. Unfortunately, Tiant did a number on my Minnesota Twins both coming and going, as the Twins gave up a young third baseman named Graig Nettles as part of the trade with the Cleveland Indians to acquire Tiant. Tiant dealt with injuries during 1970, his only season with the Twins, and the Twins released him at the end of spring training in 1971, just before he started his resurgence. Oops! I think Tiant should be in the Hall of Fame, he was a great pitcher who was overshadowed on the Hall of Fame ballot by the other great pitchers of the 1960’s and 70’s.

Maury Wills: Wills led the National League in stolen bases six years in a row, from 1960 to 1965, and he stole a then-record 104 bases in 1962. Wills got a late start, as he spent nine years in the minor leagues before finally breaking in with the Dodgers at the age of 26 in 1959. I don’t think Wills should be in the Hall of Fame. All he had to offer was speed, and while he put up a decent career batting average of .281, his OBP was .330 and his slugging percentage was .331. Okay, so Ozzie Smith’s slugging percentage was actually lower than his OBP, but Smith was a better player than Wills.

Those are my thoughts on the 2014 Golden Era Committee ballot. Hopefully the next time the Committee meets to vote on players from this era they actually elect someone.