| |

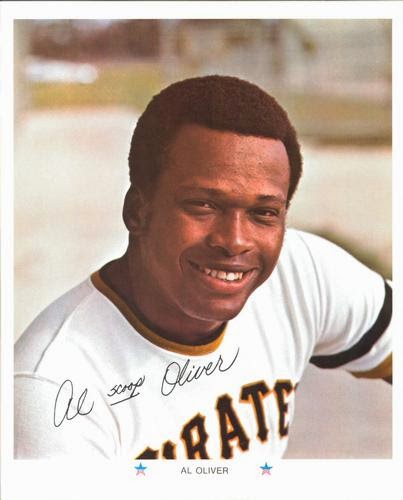

| Promo poster for Paul's album "Flaming Pie," 1997. |

|

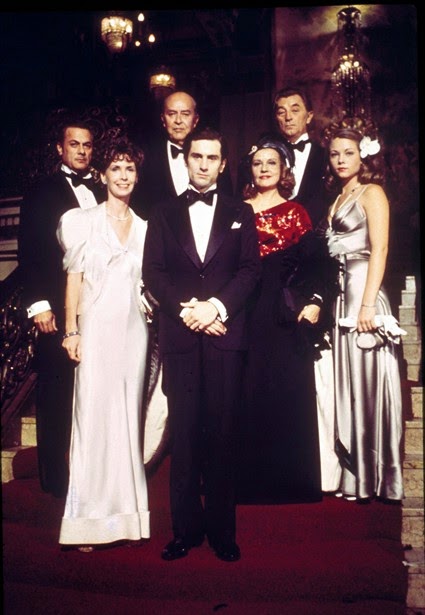

| Paul McCartney, 2009. |

|

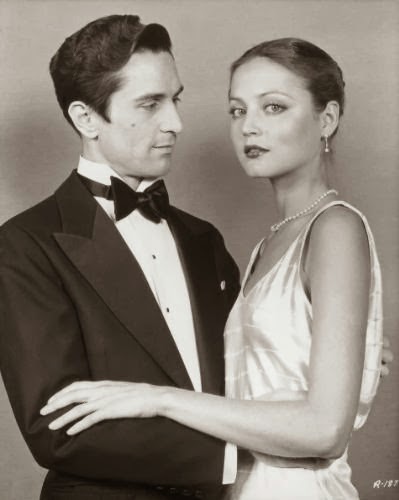

| Paul performing with Ringo in 2014. |

As I said in my previous post, Paul McCartney’s solo work since 1980 hasn’t been collected in a greatest hits compilation. So I made my own 2 disc set of my favorite Paul McCartney songs. Volume 1 covered the years 1980 to 1993, and Volume 2 covers 1997 to 2013. In my opinion, Paul McCartney has produced consistently excellent work since 1997’s “Flaming Pie.” He continues to write really great songs, and he keeps exploring new ground as a musician. While in concert Paul plays a lot of Beatles tunes, he’s never let the baggage of being a Beatle weigh down his solo career. He’s not one to dwell on the past, and I think this has helped him in his career. He’s never been afraid of taking risks, from putting his wife in his band to releasing albums of ambient music under the pseudonym “The Fireman.” The 2 disc set that I’ve made certainly doesn’t cover all aspects of McCartney’s music since 1980, as he’s also written an oratorio, various classical pieces, and a score for a ballet.

Here are the songs I chose for the second disc of “The Best of Paul McCartney: The Solo Years,” covering 1997 to 2013.

1. Flaming Pie

2. The Song We Were Singing

3. The World Tonight

4. Calico Skies

5. No Other Baby

6. Try Not To Cry

7. Lonely Road

8. Driving Rain

9. Your Loving Flame

10. Vanilla Sky

11. Fine Line

12. English Tea

13. Riding to Vanity Fair

14. Promise to You Girl

15. Dance Tonight

16. Ever Present Past

17. Mr. Bellamy

18. Sing the Changes

19. Highway

20. My Valentine

21. Save Us

22. Everybody Out There

23. I Can Bet

Some comments about the songs:

“Flaming Pie,” from “Flaming Pie,” 1997: While “Flowers in the Dirt” and “Off the Ground” got a lot of press at the time for being “comeback” albums for McCartney, I think time has shown that “Flaming Pie” is a much stronger album. In between the release of “Off the Ground” in 1993 and “Flaming Pie” in 1997, McCartney spent a lot of time on The Beatles’ “Anthology” series, and he credited working on the “new” Beatles songs for “Anthology” with jump-starting his own creativity. The title song is a stomping rocker, with a great piano part. It features surrealistic lyrics from McCartney, and the title came from a piece that John Lennon wrote for Mersey Beat about the origin of The Beatles’ name.

“The Song We Were Singing,” from “Flaming Pie,” 1997: A gentle song about Paul’s relationship with John Lennon, as Paul sings about the different things they would talk about, but how “we always came back to the song we were singing.” The lyrics sound very 1960’s, as Paul sings, “Take a sip/see the world through a glass/and speculate about the cosmic solution.”

“The World Tonight,” from “Flaming Pie,” 1997: This song has a sense of mystery about it, as we never find out exactly who the narrator of the song is addressing, and what their relationship is to the narrator. No matter, it’s a catchy song that was the first single from “Flaming Pie.”

“Calico Skies,” from “Flaming Pie,” 1997: A beautiful acoustic song, produced by George Martin. Paul sings “I’ll hold you for as long as you like/I’ll hold you for the rest of my life.”

“No Other Baby,” from “Run Devil Run,” 1999: After Linda McCartney died of breast cancer in April of 1998, Paul went into seclusion for a while. When he returned to making music, he made an album of old rock and roll songs from the 1950’s, which would become “Run Devil Run.” It’s an excellent album full of obscure songs like “No Other Baby,” which was a B-side for the group The Vipers. While the Vipers’ original was a rather brisk skiffle tune, Paul’s cover is slower and moodier, with great yearning vocals.

“Try Not to Cry,” from “Run Devil Run,” 1999: Even though “Run Devil Run” is a covers album, Paul ended up writing 3 new songs for the album. “Try Not to Cry” is very simple, but amazingly catchy. The chorus is just “Try, try, try/I try not to cry, cry, cry/cry over you/over you.” But it’ll stay in your head for days.

“Lonely Road,” from “Driving Rain,” 2001: Paul’s 2001 album “Driving Rain” is a favorite of mine. I think it has a lot of great songs on it, but it proved to be Paul’s least successful studio album in the UK, peaking at number 46. “Lonely Road” is the first song on the album, and it starts with a lovely bass intro. I’ve always wondered if this song was unconsciously about Linda, as the first verse is: “I tried to get over you/I tried to find something new/but all I could ever do/was fill my time/with thoughts of you.” Paul’s rocking vocal is terrific.

“Driving Rain,” from “Driving Rain,” 2001: Another effortlessly catchy tune from Macca. The hook is: “1,2,3,4,5, let’s go for a drive/6,7,8,9,10, let’s go there and back again.” Why is that so catchy? Paul’s gift for melody is amazing. I remember reading a description of Paul that said, “He can write a hit song as easily as most people cross the street.” Yup.

“Your Loving Flame,” from “Driving Rain,” 2001: A lovely piano ballad.

“Vanilla Sky,” from “Vanilla Sky Soundtrack,” 2001: Paul was nominated for an Oscar and a Golden Globe for this song, from the Tom Cruise movie. The song itself is light as a feather, and it sounds like the kind of confection that Paul can whip up in just minutes. “Oh, you need a song for a movie? Called Vanilla Sky? Okay, got it!”

“Fine Line,” from “Chaos and Creation in the Backyard,” 2005: For his next album, 2005’s “Chaos and Creation in the Backyard,” Paul worked with producer Nigel Godrich, best known for producing Radiohead. Paul played nearly all of the instruments on the album himself, and it’s a very strong piece of work. “Fine Line” is the first song on the album, and it was the lead single. It really should have been a bigger hit. The song is dominated by Paul’s pounding piano. Paul plays all of the instruments on it, except for the strings, and the music video imagines a band made up of many Paul McCartneys, sort of similar to his video for “Coming Up.”

“English Tea,” from “Chaos and Creation in the Backyard,” 2005: One of my favorite Paul songs. In “English Tea” Paul sends up his own image as a creator of silly songs as he sings, “Would you care to sit with me/for a cup of English tea/very twee/very me.” It’s a simple song, but very catchy and delightful. Paul’s always had a spirit of fun about him, from songs like “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “Monkberry Moon Delight,” “Silly Love Songs,” “The Pound is Sinking,” and “English Tea.” I really like that Paul isn’t afraid to indulge his more whimsical side.

“Riding to Vanity Fair,” from “Chaos and Creation in the Backyard,” 2005: Wonderful song with an incessant, melancholy melody and great lyrics. Although this song pre-dates Paul’s divorce from his second wife Heather Mills, it’s hard not to wonder if this song was about her. Sample verse: “The definition of friendship/apparently ought to be/showing support for the/one that you love/and I was open to friendship/but you didn’t seem to have any to spare/while you were riding to vanity fair.”

“Promise to You Girl,” from “Chaos and Creation in the Backyard,” 2005: Paul puts several pieces together and comes up with this catchy piece of pop. It starts out slow, with Paul playing the piano and singing, “Looking through the backyard of my life/time to sweep the fallen leaves away.” Then it sounds very Beatle-y as Paul sings, “Like the sun that rises every day/we can chase the dark clouds from the sky.” And then the piano starts pounding and it turns into an up tempo tune, all in the first 30 seconds.

“Dance Tonight,” from “Memory Almost Full,” 2007: “Memory Almost Full,” Paul’s 2007 release, was another excellent album with strong songs. Like “Fine Line” before it, “Dance Tonight” is a catchy earworm of a song that should have been a huge hit. Paul plays all of the instruments on “Dance Tonight.”

“Ever Present Past,” from “Memory Almost Full,” 2007: This song is about time moving too fast, as Paul sings, “Searching for the time that has gone so fast/the time that I thought would last/my ever present past.” It’s a nice exploration of our relationship to our own past.

“Mr. Bellamy,” from “Memory Almost Full,” 2007: This might seem to be a left-field choice, but I really like this song. It starts with horns before a jagged piano part comes in and Paul starts singing. “Mr. Bellamy” has two voices, one is Mr. Bellamy, who sings, “I’m not coming down/no matter what you do/I like it up here/without you.” The other voice is Mr. Bellamy’s would-be rescuers, who sing, “All right Mr. Bellamy/we’ll have you down soon.” It’s an interesting song.

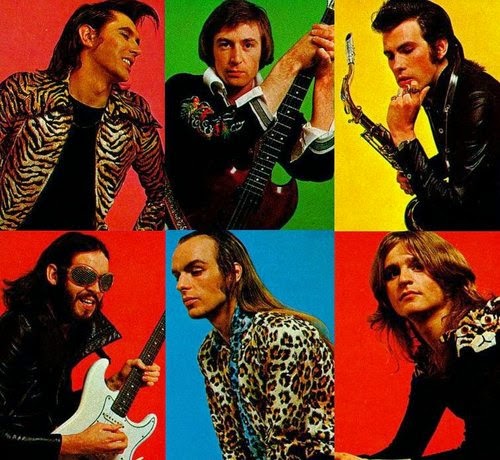

“Sing the Changes,” from “Electric Arguments,” 2008: McCartney has recorded three albums with the producer Youth under the pseudonym “The Fireman.” The first two, “Strawberries Oceans Ships Forest,” from 1993, and “Rushes,” from 1998, were ambient electronic albums. “Electric Arguments,” the third Fireman album, is more similar to McCartney’s rock records, as they have more conventional song structures and feature Paul singing lead vocals. The rule that McCartney and Youth made for the songs on “Electric Arguments” was that each song had to be finished the same day it was started. So the album was recorded over 13 days, spread over the course of a year. “Electric Arguments” is a superb album that shows Paul’s relentless creative drive. “Sing the Changes” is an exuberant song about the power of music.

“Highway,” from “Electric Arguments,” 2008: A catchy groover that tells the tale of a girl “Running through the nighttime/and looking like a wreck/got too many highlights/and a love bite on her neck.”

“My Valentine,” from “Kisses on the Bottom,” 2012: For his 2012 album of standards, “Kisses on the Bottom,” Macca thankfully chose rather obscure songs to set it apart from all the other “veteran rock star sings old standards” albums of late. True to form, Paul couldn’t help but write two new songs for the album. One of them is “My Valentine,” a lovely ballad that he wrote for his third wife, Nancy Shevell. “My Valentine” has been regularly performed by Paul in concert since 2012.

“Save Us,” from “New,” 2013: Paul’s most recent album, the simply titled “New,” is another excellent record full of good songs. “Save Us” is the first track on the album, and it’s a brisk rocker.

“Everybody Out There,” from “New,” 2013: This is another upbeat song, as Paul exhorts listeners to “Do some good before you say goodbye.”

“I Can Bet,” from “New,” 2013: Paul gets slinky on this funky one, as he sings “I’ll look you straight in the eye and pull you to me/what I’m gonna do next I’ll leave entirely to your imagination.” It’s pretty amazing that 50 years after The Beatles released “Please Please Me” Paul McCartney is still making great music.